- X

- Tumblr

Obsidian mirrors reflect shadows , as curator and artist Miguel Ángel Blanco reminds us, quoting Pliny the Elder. Two examples are currently preserved in Spain—one in the Museum of the Americas and the other in the National Museum of Natural Sciences—in addition to those found in other European museums. The obsidian mirror is a pre-Columbian object, linked in Aztec culture to the worship of the deity Tezcatlipoca (translated from Nahuatl as " smoking mirror "), the god who rules the night.

It was “a tool of sorcerers, used to travel to other times or places and to divine the future. Like books, they were receptacles of wisdom [1] .” Magical objects—which, in fact, were assumed as such by European “magicians,” as Blanco points out—sacred, ritual and almost mythical, made from an igneous rock: obsidian, a fundamental material in Mesoamerican culture.

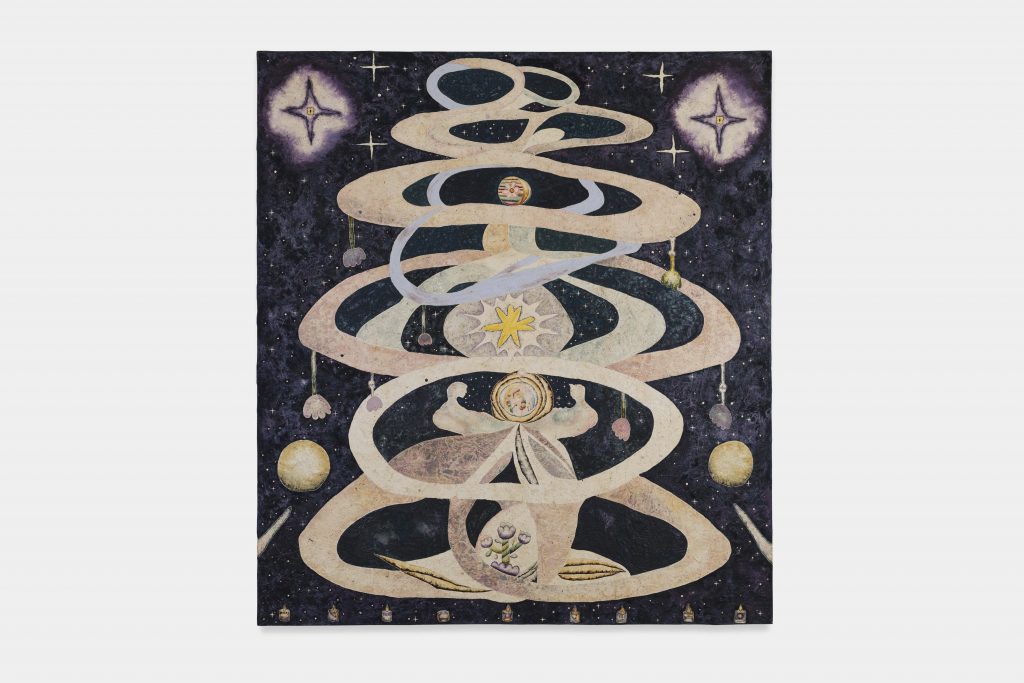

"The Way Home," 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Maya blue, Maya green, indigo blue, Brazilian wood, Mexican honeysuckle, jonote, zacatlaxcalli, kina, charcoal, turmeric, and beeswax on handmade cotton surface. 200 x 180 cm. Photo courtesy of the artist.

"The Way Home," 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Maya blue, Maya green, indigo blue, Brazilian wood, Mexican honeysuckle, jonote, zacatlaxcalli, kina, charcoal, turmeric, and beeswax on handmade cotton surface. 200 x 180 cm. Photo courtesy of the artist.That powerful Mexica element is one of the basic conceptual ideas of the exhibition by the artist Omar Mendoza (Mexico, 1993), who debuts at the Chicago gallery Povos Gallery with SOLAR SERPENT 〰OBSIDIAN NIGHT , a solo show curated by the critic and curator Victoria Rivers , where he updates all this imagery of which he is a part.

In the exhibition, Mendoza refers to the purest and most essential elements—circles, straight lines, serpentine forms—in the form of moons, suns, and other astronomical symbols that explain and order our lives. For his paintings, the artist uses natural dyes such as zacatlaxcalli, Mayan blue or green, kina, and turmeric. “When I abandoned oils and acrylics to return to collecting pigments in nature,” Mendoza states [2] , “I sought to return to the origin and question how industry and Western art have established and limited our perception of color. Working with natural pigments is, for me, an act of resistance. These colors are living knowledge that communities in Mexico continue to preserve. Using them allows me to nurture that connection to memory and feel part of a tradition that resists and transforms.”

In the curatorial text accompanying the exhibition, Rivers recounts how creation was born from a return: “When his mother whispered, ‘Those plants are still there, in your father’s village ,’ Omar Mendoza understood that his colors had their own geography.” From his father, he had inherited the patience that understands the rhythms of the craft; from his mother, the observation of nature. In that return home, transformed into research, he went back to Tlacuilotepec, Puebla, where he discovered that color arises from an ancient dance between fire and water, transmuting the muitle plant, where—according to ancient memories—they “gathered, arrived, and held council in the darkness and in the night” to give birth to color. Mendoza understood that each pigment is plant memory transformed by hands that listen, wait, and let matter speak. In this revelation, he found the origin of his method: to follow “that organic rhythm that cannot be rushed, that knows when the seeds are ready to germinate, when the colors have found their truth.”

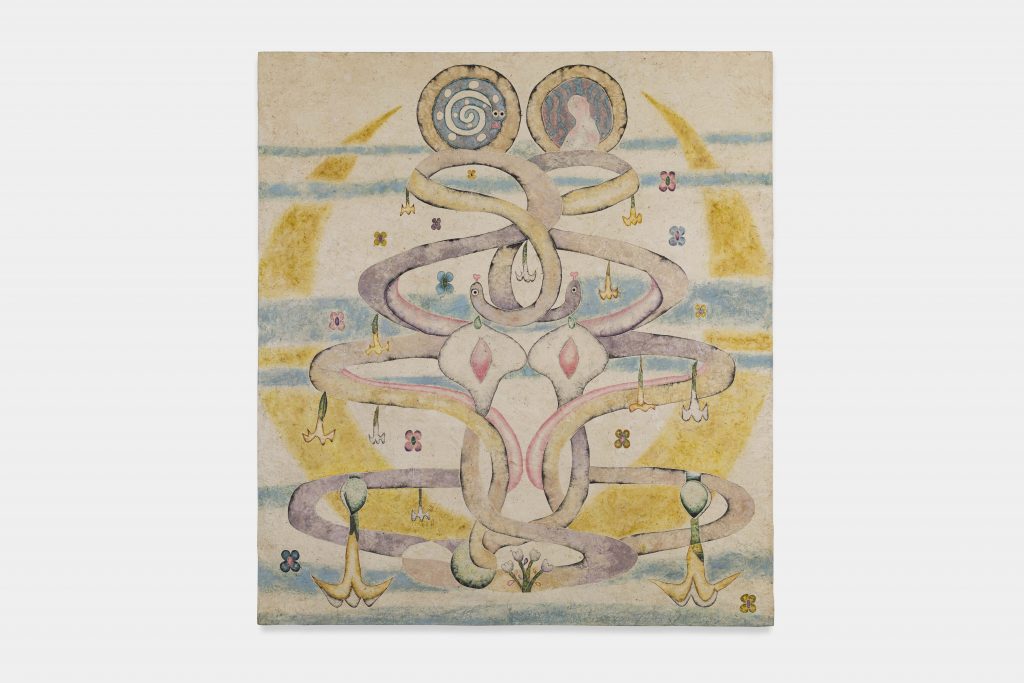

"The Floripondios", 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Mayan blue, Mayan green, indigo blue, Brazilian wood, Mexican honeysuckle, jonote, zacatlaxcalli, kina, charcoal, turmeric and alder on handmade cotton surface. 200 x 180 cm. Photo courtesy of the artist.

"The Floripondios", 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Mayan blue, Mayan green, indigo blue, Brazilian wood, Mexican honeysuckle, jonote, zacatlaxcalli, kina, charcoal, turmeric and alder on handmade cotton surface. 200 x 180 cm. Photo courtesy of the artist. Detail of "Los floripondios", 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Detail of "Los floripondios", 2025, OMAR MENDOZA. Photo courtesy of the artist.In this quest for ancestral experience, Mendoza champions a slowness that not only defines a way of working, but also a perspective on the world and how we relate to it: the time it takes for a color to exist is also part of the work . Thus, the public can observe and feel the living energy of the colors and techniques , without a fixed or closed interpretation, from those “cosmic origins where art is not representation, but distilled memory.” A literally living pictorial language then emerges—water, stone, plants, fire, night, jade serpents, stars, flowers—where painting becomes an act of reciprocity with the earth and its cycles. The artist reminds us that ancient worldviews teach that we are not above life, but within it. Understanding our origin offers us a possibility to orient ourselves toward the future with greater awareness and intention .

With a series of paintings in various formats, Omar Mendoza reminds us that true revolution lies in looking back: observing the smoking mirror , peering into its darkness, and recognizing our own reflection. In this ancestral gesture, we glimpse echoes of the visions of the British astrologer and ophthalmologist John Dee, who also sought in the black surface of obsidian a way to communicate with angels. In Mendoza's return, this gaze becomes earthly; an astral dance between matter and time, where color transforms into memory, and memory, into destiny.

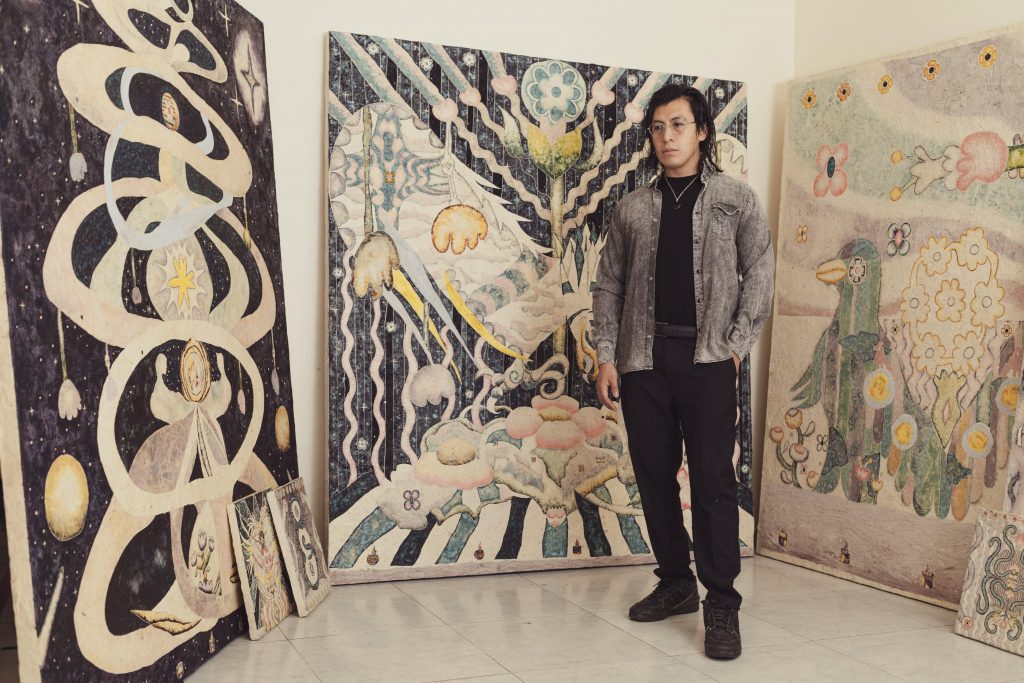

Portrait of Omar Mendoza by WAP Studio. Photography courtesy of the artist and WAP Studio.

Portrait of Omar Mendoza by WAP Studio. Photography courtesy of the artist and WAP Studio.FOOTNOTES

[1] To quote again the words of the aforementioned Miguel Ángel Blanco, who in 2013 curated Natural Histories , where he took the two obsidian mirrors that are in Spanish museums to be part of the exhibition.

[2] In a conversation between sirocomag and the artist regarding this article.