The title of Isabella Mellado's show Te Diré Quién Eres (I'll Tell You Who You Are) draws you into this line of questioning-are you a heretic or not? Witch or not? With us or not?

Image: Isabella Mellado, The High Priestess, 84×90″ oil on canvas (detail). A seated figure in front of a light blue sky, wearing a pink feathered mask and holding tarot cards in two hands and a green cat in a third arm. A thick border made up of pink stars on light pink squares surrounds the figure. Courtesy of Povos Gallery Chicago.

Stepping into Isabella Mellado's current show at Povos Gallery is to find oneself among shapeshifting portraits of saints, gargoyles, and tarot's major arcana. The title of Mellado's show Te Diré Quién Eres (I'll Tell You Who You Are) draws you into this line of questioning-are you a heretic or not? Witch or not? With us or not? The full line is something like the well known quote: tell me the company you keep, and I'll tell you who you are. It is a proverb with roots dating back to Aesop, Euripides, and others, though it is often attributed to Miguel de Cervantes; the line appears in Don Quixote in a scene where Sancho Panza tells Don Quixote it is no wonder that being among enchanters and the enchanted that one would act as they do.

The figures in Mellado's art transcend localization in space and time as their bodies multiply to appear at once in several guises and positions, including auto-affectionate embrace. From the sigils they hold-a beetle, a deck of cards, a silver cup-to the discipline of their postures, these are undoubtedly portraits of a kind of spiritual transcendence. It is clearly, however, not a transcendence that would forsake this world as an ashen waste through which we pass en route to the next, but rather, a transcendence firmly situated within a world of lush, inviting texture and life. That is, Mellado's witches and saints live among rocks, trees, and flora that inscribe shadows on their skin or take the place of their face in intimate connection.

Mellado draws inspiration for these scenes from growing up in Puerto Rico, local folklore and religious art writ large, and from her experience as a queer artist living in diaspora. Occult practices and bodies of knowledge like tarot and astrology are ubiquitous in queer culture and dating, aligning the heretical nature of fortune telling, witchcraft, and queer sociality. Mellado's Te Diré Quién Eres therefore reads as a question of practice-bound kinship in the context of her paintings.

In a now famous interview, "The Gay Science," for one of the most important gay magazines of its time, Le Gai Pied (Gay Foot), Michel Foucault makes use of the same proverbial phrase, this time to describe the way in which the science of sexuality functions as a form of power that shapes our desires and renders us intelligible as social subjects: Tell me your desire, and I will tell you what you are. It is as if, he says, this system of knowledge and power says to us, "Tell me your desire, and I will tell you what you are, if you are normal or not, and thereby I will validate or invalidate your desire," validating or invalidating you as a subject (Foucault, "The Gay Science," 389 translation modified). This imperative, tell me your desire, is a defining feature of what Foucault calls biopower-a form of power that renders the life and body of the individual and the population subject to minute calculations and administration. Coeval with the spread of capitalism as a globally hegemonic social and economic form, we find the science of sexuality as one of the primary points of power's investment in the body, especially in the way that it locates individuals on a spectrum in relation to a norm.

"Queerness itself is a kind of heretical practice that shape shifts to evade categorization and to refuse administration and definition."

Now, when we hear Te Diré Quién Eres, it is as if whispered by Mellado's witches and saints. The magician, for example, sits on a rocky ledge in a forest with their legs multiplied into three visible sets, the thin fabric of one dress draped and stretched between them. The magician wears a kind of green leather gargoyle mask that covers the mouth as if it had been sealed mid speech, but this too is doubled. While the mask covering the magician's face reveals black holes where one would expect to find eyes, there is another mask, transparent, hovering above the head of the magician, with eyes animated by the sky peeking through the trees. There is a dagger, a silver chalice, and a dead beetle that Mellado found in Tuscany while staging the photograph on which the painting is based. We see three hands, the furthest removed of which resembles the ardhapataka mudra, which, among other things can symbolize the bank of a river and the bridges we might build across it.

The magician, like many of Mellado's portraits, is shape shifting. This in and of itself might lead us to describe the magician as a queer figure-impossible to pinpoint in the midst of transformation, literally bridging their own multiplicity. Queerness itself is a kind of heretical practice that shape shifts to evade categorization and to refuse administration and definition. It is a refusal of the imperative Tell me your desire, and I'll tell you what you are. In fact, we can define Foucault's ethical rejoinder to biopower in part by the imperative "to make ourselves pleasurably, erotically strange," (Lynne Huffer, Mad for Foucault, 253).

How do we become "pleasurably, erotically strange?" We do so through what is for Foucault a spiritual practice of confronting limits, borders, and boundaries in such a way that we are changed in the process. Mellado's witches and saints are portrayed in precisely such spiritual practices of disrupting the boundaries of the body and challenging both what we know and how we know it. The High Priestess, for instance, reimagines the Catholic seraphim. Traditionally, the seraphim are six winged angels only ever referred to in the plural as a host that surrounds and sings to the lord. They are associated with a rousing heat of tireless activity and enlightening clarity. Mellado's seraphim is set in place of the high priestess' face, arranged as a six-pointed star of pink and peach feathery yet leafy wings that do not quite join in the middle. Your eye is drawn to investigate the point at which the rest of the host of seraphim might lie in an almost vertigo-inducing experience where what is visible and what is hidden collapse into one another at the heart of the seraphim now removed from the heavenly coterie. Their light is brought to bear instead on the figure of the high priestess as a symbol of sacred knowledge and intuition.

"Te Diré Quién Eres becomes both a challenge and an invitation surrounded by portraits of spiritual transformation and boundary breaking."

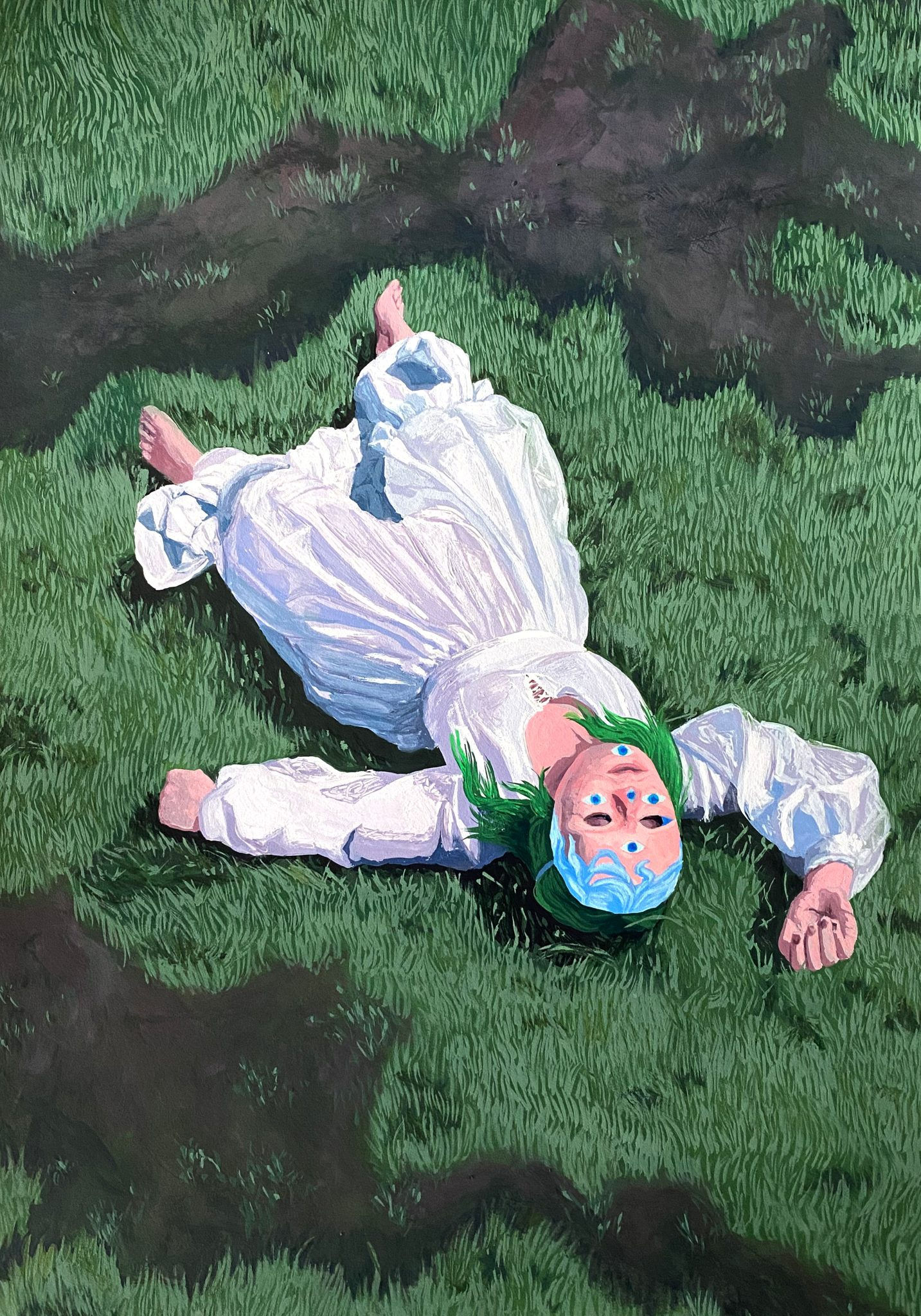

Seriously confronting the queer character of the multiplicity of Mellado's witches and saints is to find oneself in "our mixed vocation as apostle and interpreter," called to "a prophetic, promiscuous 'spiritual' thinking at the edges of thought" (Foucault, Madness 537; Huffer, Mad for Foucault 273). It is to become part of the company that the title of the show interrogates. It is to find oneself in a moment of desubjectivating pleasure like in The Aftermath, a painting of a masked woman in grass that undulates with the kind of patterned breath of movement that a psychedelic trip, that a new way of seeing and feeling, might reveal. Te Diré Quién Eres becomes both a challenge and an invitation surrounded by portraits of spiritual transformation and boundary breaking. It suggests an invitation to become multiple oneself so that I cannot tell you who you are, or if I can, it is only precisely through a kind of queer Foucauldian ethic of spiritual self-transformation.

Footnotes

Foucault, Michel. "The Gay Science." Trans. Nicolae Morar and Daniel W. Smith. Critical Inquiry , Vol. 37, No. 3 (Spring 2011): pp. 385-403.

-Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Random House, 1965.

Huffer, Lynne, Mad for Foucault: Rethinking the Foundations of Queer Theory, New York: Colombia UP, 2010.